It’s summer and the school year has ended… we had kindergarten graduation, high school graduations and college graduations. At this point, you know your students so well, maybe you can even picture what they’ll be doing when they’re adults. So, close your eyes and picture your class. Which of your students do you see having “executive” skills?

No, I’m not talking about students who will end up as our future CEOs, COOs or CFOs. The reason I bring this term up is because I recently learned more about the neuroscience of “executive function” at the Teaching & Learning Conference, and I can’t stop wondering if I’m doing enough to support my students in mastering their own brain power.

Executive function is a term used by brain researchers that describes how well the brain manages self-control, uses working memory and exhibits flexibility. That term does actually describe some of the traits that it takes to be an “executive” in a company. Executives are often expected to be in charge, experts in their field and capable of responding to any situation.

Executive function is a term used by brain researchers that describes how well the brain manages self-control, uses working memory and exhibits flexibility. That term does actually describe some of the traits that it takes to be an “executive” in a company. Executives are often expected to be in charge, experts in their field and capable of responding to any situation.

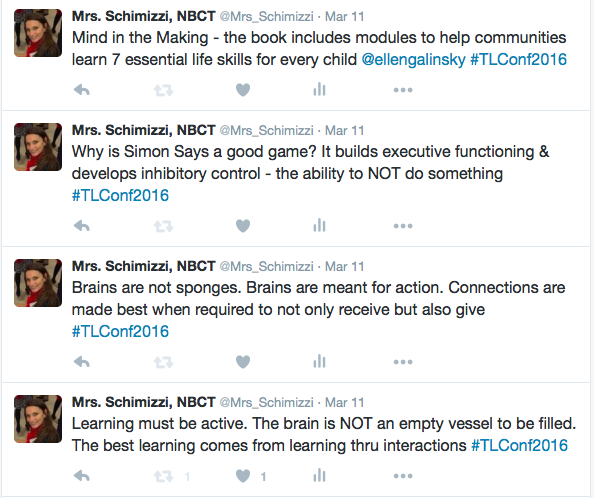

So, what does it take to build executive function? In the session called “Brain Research in Action: Policy and Practice Implications of Developmental Science on Accomplished Teaching,” I heard Ellen Galinsky, Jonathan Gillentine, Steven Hicks and John Holland speak about how the brain develops. When they mentioned the term “executive function,” I realized I was missing an entire part of my understanding of how brain development impacts student performance, behavior and interactions. I found myself tweeting up a storm, and eagerly bought Galinsky’s book, Mind in the Making.

The terms inhibitory control, self-regulation, goal-directed behavior and task persistence were a bit unfamiliar, even for a biology major like me. Thankfully, the wonderful presenters offered specific tools and examples that made this topic not only interesting but also accessible.

During the session, Ms. Galinsky shared information about an app she helped design, called Vroom. They showed us the video about the app (at the bottom of the Vroom website), and I was suddenly crying. While the video is about how all parents have what it takes to be “brain builders,” I kept thinking that all teachers have what it takes to be brain-builders, too. The app suggests a variety of easy steps to help children develop executive function, and also explains the science behind the actions. Having recently become a mom, I was further drawn to the ability to personalize the app using your child’s name. These tips and hints were all the result of Ms. Galinsky’s research on how to help build the brain’s pathways and power.

Jonathan Gillentine took the time to talk about how executive functioning can also be fostered through inhibitory games (like “Simon Says”) and through creative play – for example, younger children can build executive function through games like what Cookie Monster does while he’s waiting to eat his cookies!

But what about our older students? Don’t worry – there are still so many ways that we can reach all of our students to help them learn how to harness their brains and build their capabilities. Below are three educators’ views on how executive function can be fostered in schools.

Lauren Sabo, an NBCT who coaches other teachers, shares how she sees teachers in her school supporting executive function.

Student motivation is an issue at my school, so this year we did a book study on Growth Mindset, so that teachers could recognize the characteristics of fixed mindset in students, and use strategies to create a more flexible mental capacity. One thing we do is host a weekly advisory period that follows the Monday Morning Meeting framework. As a class, the teacher facilitates a friendly, but focused discussion to begin the week as a cohesive unit. Each week, students revisit goals from the previous week, reflect upon the achievement of those goals, and set new goals for the current week. The goals can be personal, behavioral, or academic, based on the student’s reflections. We have found goal-setting activities to be important to a student’s mental flexibility. Through goal-setting–and most importantly, how the teacher facilitates the reflection process with students as they revisit their goals–students begin to see that we all begin at different places and that’s OK. The path you take to reach your personal goals is what is most important to your own success.

Lauren Schultz, a media specialist at a high school, see similarities between how she interacts with her students and with her own son.

As a parent and a teacher, I find that I teach working memory in a similar way despite the fact that my child and my students are of different ages. For both, I have found that they commit information to memory easier through a hands-on application of the skills that they are trying to learn in context. The context aspect is key; if students or children have not used the skill in context before, then it will be hard for them to draw on the previous experience and apply it to a new experience. However, if they are already familiar using that skill, then they can begin to apply it to other situations. Oftentimes, reminders that they have used the skill before in a circumstance help them to apply it to a new situation.

William Hayes, a principal at East Camden Middle School, explains how executive functioning goes beyond just academic performance to also grow students as a whole.

One of the simplest ways for teachers to help build executive function is to support students in the process of questioning and self-reflection. Too often teachers provide reactionary consequences and neglect to explore a child’s feelings, thinking, and rationale behind their decision-making. Such an exploratory process allows both the teacher and the student to learn and develop from past mistakes, misconceptions or misinterpretations.

I’ve found that while not everyone may know the term “executive function,” most people know about self-control, working memory and mental flexibility. It’s so exciting to realize all the ways that we can help our children in our homes and in our schools as they grow their minds. It might be in structured ways like a card game or in imaginary play where they make their own rules. We all have what it takes to be brain builders!