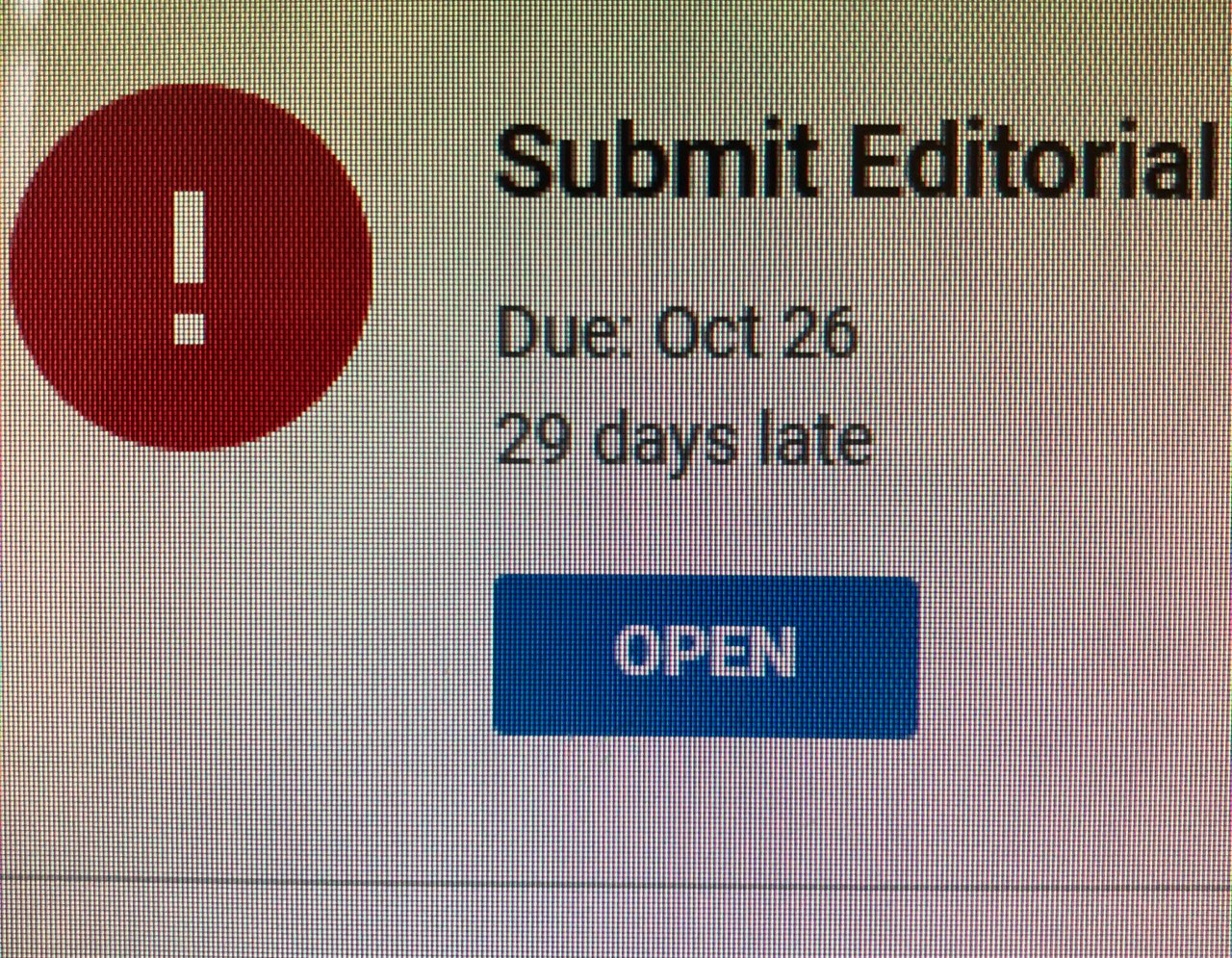

Above: My journalism student finally turned in his editorial. I didn’t lose anything by letting him turn it in late. This was an accomplishment for him and–even though it was almost a month late–he felt proud of himself.

Above: My journalism student finally turned in his editorial. I didn’t lose anything by letting him turn it in late. This was an accomplishment for him and–even though it was almost a month late–he felt proud of himself.

A couple of months ago, a high school senior taking graduation photos came up to me in the hallway and desperately asked, “Can you tie my tie?”

I answered, “Nope. But I can teach you how.”

“But the photographer is waiting,” he responded.

I said, “Then you better learn fast.”

One of the disappointing changes I’ve seen in my 23-year career in Chicago Public Schools is that we’ve gotten to a point where we save students academically instead of teaching them how to save themselves.

I know. Things were worse in 1995 when I started teaching. Thirty percent of Latino students, for example, dropped out of high school then. In 2016, only 10% of Latino students dropped out.

One way to predict student success is grades. In “The Predictive Power of Ninth-Grade GPA,” we learn that “the research on high school grades suggests that grades are not only good predictors of important future outcomes—such as high school graduation, college enrollment, and even college graduation—but they are also better predictors than standardized test scores.”

About eight years ago, I started hearing about “no zero policies:” a belief in the idea that students should get 50% credit for work they did not do. This practice, advocates argued, prevented students from falling into a hole that they could not get out of. Fifty percent on a 100-point scale, after all, still equals failing. Lots of 50s should still equal an F for students so a zero isn’t necessary.

Mathematically, yes, this proves true.

But no-zero policies don’t teach students the independence or self-advocacy skills they need to succeed outside of our classrooms.

While no-zero policies might help students improve their GPAs, these policies, I argue, work against what the Consortium explains in “Teaching Students to Be Learners” as the other factors influencing a student’s academic identity: “the ways students interact with the educational context within which they are situated and the effects of these interactions on students’ attitudes, motivation, and performance.”

I’ve always taught high-school English classes with a philosophy of “Reward them for what they’ve done.” But if they don’t do anything, if they’re absent, if they don’t show me they’ve mastered—or at least attempted to show me how much they learned—I cannot reward them with 50% credit.

Instead, I give zeros for missing work but still ensure that students have the opportunity to succeed.

This is how I carry out this “Yes to zeros” policy in a socially responsible, culturally conscious way.

Use Standards-Based Grading

In my English classes, a large percentage (70% of the final grade) of a student’s grades consists of how well a student demonstrates understanding of a concept as assessed according to specific academic standards. I grade them on the specific skill–not on the assignment as a whole.

Does the writing exceed expectations and can it be used as a close-to-perfect example for other students? It’s an A.

Does it meet expectations with minor areas for improvement? It’s a B.

If it’s basic and predictable, it’s a C.

If it’s incomplete and shows misunderstanding, it’s a D.

Anything below that is an F.

But not every assignment is worth 100 points. A student’s first attempt at thesis-statement writing, for example, might be worth 50 points. The second and third attempts will be worth 100. The more practice students and support students receive, the higher the stakes.

Many teachers make every assignment worth 100 points. But I don’t see how a grade for an exit slip that took 3 minutes to complete should carry the same weight as a paragraph they worked on for 45 minutes.

If students don’t do an assignment due to a reasonable explanation (a excused absence because they were sick), I leave it blank in the online grade book.

If, however, they cut class, that’s a zero. Down the road, if they show an understanding of the concept, I might go back and change the zero.

When students get multiple attempts on an increasing scale, a few zeros for missing an opportunity to succeed won’t put the student in an academic hole.

Formative vs. summative

I always accept the big writing assignments—the summative assessments–which are usually assigned 2-3 times per quarter, even if they’re super late. If I don’t accept them, these summative assignments, where students demonstrate learning of multiple standards, will put students in a hole if they do not turn them because they’ll get three to five zeros.

If they’re in class, students receive the instruction, the support, the feedback, and opportunity to succeed with these assignments where they must demonstrate the highest level of learning.

Therefore, if they don’t turn these big writing assignments in, there’s no way I can justify giving students 50% credit for these complex opportunities.

Right after the deadline if the assignment was not turned in, I fill in zeros to create a sense of urgency for the student—not for me. And let me tell you—receiving five zeros for a multi-page writing assignment they were supposed to work on in-class and out of class for two weeks gets them thinking about how to save their grade. If it doesn’t, there are usually other factors in this students’ mindset or life situation out of my control.

Still, the opportunity to turn these in exists. Which is why I never have big writing assignments due at the very end of the quarter or semester. That creates situations they cannot get out of if they don’t turn them in.

But What about the Homework and Other Stuff?

Homework and participation goes into the smaller performance categories (30% of the final grade) because these things should not be the cause of an F. So, yes, students can earn a passing grade if they don’t do homework. And they can still pass even if they don’t do every single assignment. But they probably won’t end up getting an A or B.

By focusing more of our attention on the 2-3 bigger assignments each quarter, I cut down on the amount of late work I need to be willing to collect.

Has this ever backfired? Nope. The handful of students who got an F from me over the years missed class a lot or never turned in any work.

In fact, giving zeros for big assignments taught students to make more effective decisions when faced with difficult circumstances. Sometimes we can’t do it all. I certainly can’t. Students learn to do what they can to succeed.

Last week, a student asked me if she could turn in an overdue research paper. “Sure,” I said. “When will you give it to me? Tomorrow? Friday?”

She stared at me. “You don’t care?”

I jokingly asked her if she wanted me to explode in rage because the paper was late. I raised my finger in the air and pretended to yell. “Is that what you want me to do?” I giggled.

She didn’t know what to say.

I want my students to be the ones problem solving when assignments aren’t turned in—not me. Again, they must save themselves. Besides learning to write, I want my students to learn to focus on the self-advocacy skills they need to succeed in more places than our classroom. It takes social skills and courage to ask for an opportunity. My students need to be confident enough to do that—on their own.