Of the National Board’s Five Core Propositions, teachers being part of learning communities was long the toughest for me as an NBCT teacher-leader to connect with, largely because of my schema around what “learning community” should mean.

For a dozen years, we have been a DuFour Professional Learning Community (PLC) District. We’ve carved out time for teams to meet, but in those dozen years of “implementation,” the systems as constructed were producing what one of my colleagues accurately described as “Professional Compliance Communities.”

For years, our PLC system felt like hoops we teachers were obligated to leap in order to serve some ambiguous directive of someone at a higher pay grade. The premise of PLCs – that they would help us improve our practice as teachers – was rarely realized, if even considered. Authentic learning in an authentic community didn’t seem to have a place in the very system ostensibly designed for that purpose. We’d fill out the forms, submit the data reports, and then retreat to our classrooms, our practices unexamined and unchanged.

Teachers being part of learning communities, as a core proposition of NBPTS is foundational to creating the conditions in which accomplished teaching can occur. When I think about our “Professional Compliance Communities,” it is clear we had a system and it was producing a certain result: Generally dissatisfied teachers still working in isolation, a perceived obsession with “accountabalism” rather than improvement, and a profound disconnect between PLC work and classroom practice.

Seeing those outcomes, instructional leaders have attempted to lead change over the years, manifested as new discussion protocols, new requirements, or new forms to fill out. Yet, none of these procedures changed the outcomes because none of them significantly changed the system. Nothing seemed to stick: Improvements were fleeting, and even those improvements could be attributed to other factors, or combinations of factors.

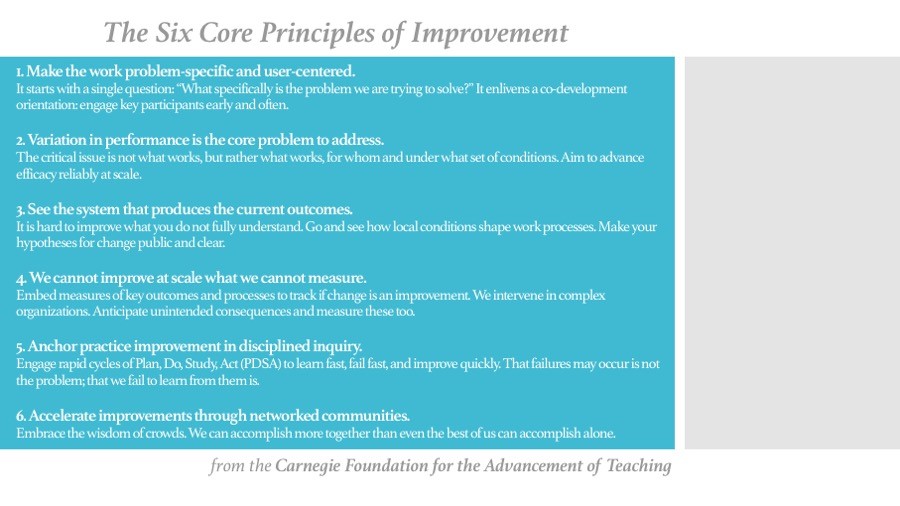

This year has been a little different. Through my district’s work with the National Board’s Network to Transform Teaching NT3 work, I’ve had the chance to learn about “Improvement Science,” which focuses on how complex and complicated human systems can be improved in a way that endures. Of the many concepts that resonated with me, the six core principles of improvement echoed most profoundly. (They likely resonated with others, as our NBPTS staff leads provided them to us on a laminated card.)

These core principles of improvement are drawn from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and are fleshed out thoroughly in the book Learning to Improve: How America’s Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better.

In my work with H.B. Elementary (our NT3 Pilot School which I serve as an NT3 “Improvement Lead”), our team of administrators and teacher leaders have eagerly applied the principles of improvement, starting with seeing the system. The leadership team took a close look at the systems producing the current outcomes, and quickly recognized what had been getting in the way of success with PLCs. Out of a well-intended effort to “take something off of teachers’ plates,” administrative leadership had taken on the design thinking around PLC structures, protocols, and expectations. What this did in essence, though, was strip teachers of any sense of authority or agency in their collaborative work. Furthermore, we realized that prescribing the composition of the PLC teams resulted in interpersonal conflicts that were unproductive, and left unaddressed: Every room had its own unique elephant.

True leadership means a willingness to challenge assumptions and make significant change, and this is what the leadership team at H.B.E. has chosen to do. By embracing the core principles of improvement, they are building the foundation for enduring systems transformation. Where the previous system limited teacher agency and autonomy, the new system has these at its foundation. Where the previous system had no place for considering the “how” of collaboration and team dynamics, the new system has embedded intentional learning about operational preferences, predictable group tensions, and understanding divergent collaborative styles. Where the previous system demanded production and reporting of data, the new system emphasizes meaningful use of diverse types of data to inform collaboration and instruction.

Each of these changes was rolled out individually and deliberately, one at a time, so that the impact of each new shift in the system could be monitored and considered. We are only half of a school year into this work, and we’re already seeing a dramatic shift in how teachers characterize the value and function of their collaborative teams.

Achieving this change required an honest look at the existing system, to recognize how the system itself, and not the people within the system, produced both positive and negative results. Increasing the former and reducing the latter is the work of improvement, and I now feel like we have some core principles that will not only guide further improvement, but also help our efforts to endure.